Zhang Wenhai's art of the possible

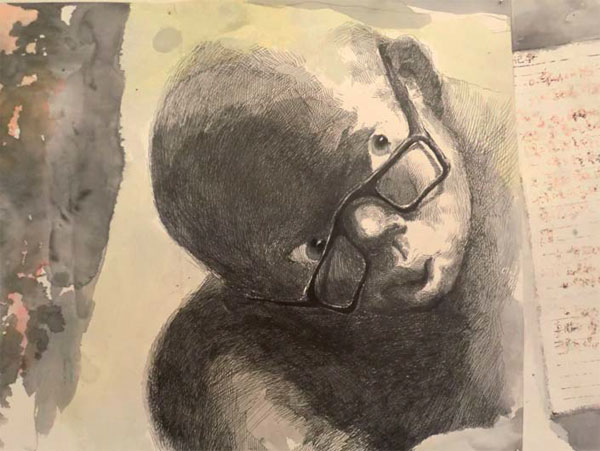

| An example of Zhang's work. Provided to China Daily |

| Zhang Wenhai teaches traditional Chinese paintings in his Brussels studio. |

Chinese printmaker and teacher introduces students in Belgium to a new world

Anyone stumbling upon the Churchill Studio in Brussels could be forgiven for thinking that when they step inside they will see wartime paintings in the colors of blood, toil, tears and sweat. The studio is, after all, in Winston Churchill Avenue.

But those in the know will be aware that the studio is devoted to Chinese art. Which of course means that what will first strike the eye will be paintings of birds, flowers and mountains, with the obligatory calligraphy. Wrong.

What many visitors will first see after they step through the front door is a wall covered in sketches depicting one man's life working in restaurants.

That man is Zhang Wenhai, the studio owner. To be sure, traditional Chinese paintings hang on the studio's walls, but it is Zhang's restaurant sketches that he is keen for visitors to see first.

Zhang worked in those Chinese restaurants in Brussels during his first seven years in the country, when he was studying for a master's degree in printmaking at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

Doing such work, including waiting on tables, delivering food and washing dishes, is common for some newcomers from China to Belgium, he says.

For it was in doing such work, he says, that he learned the local language, was able to observe the minutiae of life in everyday Brussels and most importantly, came to realize that life is as much about giving as taking.

He particularly recalls the day he presented and defended his thesis and was awarded his master's degree. Anyone else might have gone out in the evening to celebrate, but Zhang ended up back at the Chinese restaurant doing yet another shift.

"It was as if the academy and the Chinese restaurants were on different planets," he says.

"Once you entered the restaurant, you were under its influence, whether you were an artist or something else. It dragged you into its orbit."

Peering through a tiny food delivery bay in a restaurant kitchen gave him an insight into the relationship between the Chinese in Brussels and wider society, he says.

In the eyes of his workmates he saw people struggling to cope with their new surroundings, but extremely keen to learn more about them.

It was then, he says, that he decided to bridge those two worlds through his art.

The result is a thriving studio that offers classes in Chinese traditional art every weekend. His bridge building also includes giving lessons at Confucius institutes in Brussels and Liege and at other schools.

In one part of Churchill Studio, which is in a two-story brick building, brushes of all sizes hang on a wall overlooking eight large tables on which students do their work.

In a typical lesson you may see five or six Westerners painstakingly reproducing Chinese calligraphy, without necessarily knowing the meaning of the characters they are painting. For them the most important thing is to feel the spirit of xie yi, or freestyle, writing, using charcoal or thinned paint to reproduce the subjects on canvas.

The people Zhang teaches can be as young as 5, and they come from all works of life and from all over Europe.

It is common for the younger students to have at least one parent who is Chinese. The aim is for the children, immersed in European life, not to lose contact with their Chinese roots. In some ways, the children's competence in Chinese painting is of secondary importance; the main thing is that they can mix with other Sino-European children in comfortable surroundings.

Most of Zhang's older students are female, among them Therese Zaremba-Martin, a retired French interpreter.

Before attending Zhang's lessons, she says, she had studied works of the Chinese philosophers Zhuangzi and Laozi and taken Japanese calligraphy lessons. Every Saturday morning at the studio she spends three hours trying to replicate the works of Chinese master painters.

One thing that appeals to her in the art is the harmony with the nature that it expresses, she says.

"While I am drawing, I am 'in' the paintings, breathing and feeling, not at a distance just learning about the art and its techniques."

Another student is William Frei, who was Switzerland's consul-general in Shanghai for four years until 2010. It was there, he says, that he started to learn two important techniques of Chinese painting: gong-bi, a method using very fine brushstrokes, and shui-mo, a style of watercolor or brush painting.

After arriving in China he realized similarities in Western water-color painting and Chinese painting, he says.

He now paints Swiss mountains and landscapes using strong or soft lines, ink wash, sharp or dotted brushstrokes.

"You have to be careful, because in Swiss mountains, there are no trees, purely rocks and snow The shapes of mountains are different and we do not have water cascading from mountain tops."

Zhang, from Beijing, first learned traditional Chinese painting, when he was very young, at the home of a master. But soon, like many young Chinese under pressure with schoolwork, he had to give it up. Later he learned animation and Chinese painting in Chinese fine art schools.

He was drawn to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels to study printmaking. He started there 14 years ago and has been in Brussels since. He had always wanted to learn oil painting, too, he says, but found the European masters were too imposing.

Zaremba-Martin and Frei say Zhang is not only an outstanding artist but a good teacher.

"Zhang explains the philosophy behind the art and gives the Chinese context, and communication with him is a two-way thing," Zaremba-Martin says.

What the two may be unaware of is that Zhang has struggled to find a way to make the concept of Chinese painting clear and to adapt his teaching to suit individual students.

With Chinese painting and calligraphy, students have to learn by rote by copying or trying to replicate the works of the masters in minute detail again and again. These days, the efficacy of that traditional method is often challenged by those who put a premium on creativity.

Zhang says that when he started teaching, Western students would often make it clear that they did not like a particular Chinese master's work, something he says a Chinese student would never do.

At the beginning, Frei often challenged him with questions, for example, about the position of objects or perspective.

Zhang says he was indulgent with such objections and queries, not wanting to impose his Chinese way of teaching or learning on the students. Instead, he says, like all the ancient Chinese masters, he adapted the teaching to each student.

Through constant communication, negotiation and adaptation Zhang and his students say their lives, including their artistic styles, have been enriched.

China Daily

(China Daily European Weekly 04/04/2014 page28)

Today's Top News

- Takaichi must stop rubbing salt in wounds, retract Taiwan remarks

- Millions vie for civil service jobs

- Chinese landmark trade corridor handles over 5m TEUs

- China holds first national civil service exam since raising eligibility age cap

- Xi's article on CPC self-reform to be published

- Xi stresses improving long-term mechanisms for cyberspace governance