'We have history of working with businesses'

| David Greenaway says it is important for academic research to be shaped by needs of businesses and industries. Cecily Liu / China Daily |

Western universities' track record of commercializing research gives them a head start, says academic

David Greenaway, vice-chancellor of the University of Nottingham, says Western academia can play a crucial role in facilitating China's transformation to a knowledge economy.

The 60-year-old economics professor insists that China is now at the crossroads and only a new generation of critical and creative thinkers can help to sustain its spectacular growth rate.

"In moving toward a knowledge-based economy, China needs innovation. Behind innovation is education, critical thinking, creative skills and risk taking," he says.

"The link with the academic sector is very important, because when a company develops new products which they feel confident are reliable and innovative, they need to do basic research, and the basic research tends to start at universities."

He says that Western universities' established history of commercializing academic research gives them a head start in China, where market-driven academic research is just beginning.

In 2004, the University of Nottingham established a campus in Ningbo, in East China's Zhejiang province, in collaboration with the Wanli education group, effectively creating the first Sino-British hybrid university.

Alongside its teaching commitments, the university has also helped dozens of Chinese businesses strengthen technology development.

"They are hungry to upgrade their technology. They are hungry to find better ways of organizing themselves, and develop new products - because in a competitive world, it's not just about new innovations, but how quickly you take these innovations to market," he says.

For example, China's AVIC Commercial Aircraft Engine Company is currently working with the university's researchers to find ways to improve its fuel efficiency and the environmental performance of its aircraft.

Another reason why Chinese companies work with the university is to expand into international markets, as the university's research team better understands Western industry standards and consumer taste, he says.

One such example is the Chinese food and beverage giant Hangzhou Wahaha Group, which the university is helping to develop new products for China's increasingly health-conscious and international consumers, as well as improving its quality-control processes through staff training.

Other Chinese businesses working in partnership with the university include the oil and gas giant PetroChina, Chang'an Automobile, animal feed producer New Hope Group and the railways manufacturer China South Locomotive and Rolling Stock Corporation Ltd, just to name a few.

"It is important for academic research to be shaped by the needs of businesses and industries. This connection can reform the way research is done."

Such a view is in the forefront of Britain's education sector, where historically, academic research outcomes are seen as the end rather than the means.

Greenaway says he has noticed Chinese universities working increasingly closely with businesses, and more and more high-tech parks are being built across the country, but he believes the University of Nottingham has a distinctive advantage.

"Here in Nottingham we have a long history of working with businesses, including big companies like GlaxoSmithKline, Rolls Royce, Alliance Boots, AstraZeneca, and so on. So we have a lot of experience we can bring quite quickly into the context of what is still quite a young university in Ningbo.

"The research skills we develop in the UK are very transferable when delivered in China. Our leading researchers will go to Ningbo for a period, and if the infrastructure and equipment are already in place, they can get on quickly with their research, and help develop young researchers in Ningbo."

He points out that Western universities also help China's economy by cultivating young talents who champion individuality, leadership and creativity, as opposed to pure academic success.

"What may be a potential barrier is a fear of failure," he says on China's current young generation talent pool, after a question on "when should China expect its Bill Gates or Steve Jobs" from a Chinese contact prompted him to give the topic some thought.

"It's interesting he picked these two people because Bill Gates dropped out of college, and Steve Jobs failed the first time he sat (college exams), but went back again. They're in a culture where failure is not disgrace, it's a way of learning, and if this particular idea doesn't work, well, we move to the next one. You need to take risks," he says.

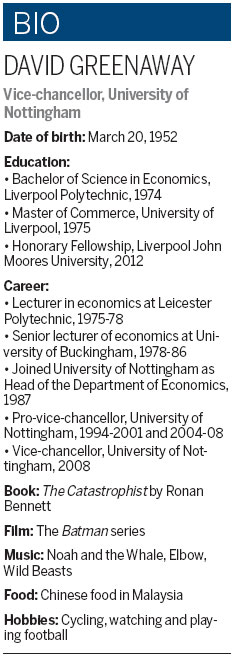

Born and raised in Shettleston, Scotland, Greenaway studied Economics at Liverpool Polytechnic and later the University of Liverpool. He subsequently held academic posts at Leicester Polytechnic, the University of Buckingham and joined the University of Nottingham in 1987.

Alongside his academic career, he has also advised a number of public bodies and international agencies, including the World Bank, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the World Trade Organization and the United Nations.

As an economist who has spent a fair amount of time analyzing developing economies, Greenaway says that he admires China's speed of growth. "I've not seen a country as fast in developing as I've seen in China," he says.

He says he feels the world economic downturn is providing Chinese companies with good opportunities for international expansion.

"Growth is slow in the West, so Chinese companies can come and acquire Western companies. The key is finding the right environment where Chinese investment is welcome - and the UK is one."

The sectors where Chinese companies are strong domestically are likely to be the same ones they succeed in internationally, he says. These include, in particular, energy technology, electronic engineering and food and drink.

Such a generalization holds true certainly in Europe, where IT companies like Huawei and ZTE are rapidly gaining market share. This year also witnessed China's Bright Food Group Co acquiring control of British cereal maker Weetabix Ltd, gaining key technology and robust sales channels for its own products in Europe.

But Greenaway observes that the flip side of China's unprecedented pace of international expansion is the challenge it creates for institutions like the WTO to satisfy its needs, for example, on the issue of trade disputes.

"Protectionism is always a concern. We're going through a period where we're seeing more of it. That's disappointing. We know from history, it's not an effective policy," he says, making reference to the post-World War I 1930s economy when many countries tried, but failed, to protect domestic employment through protectionism.

One example of a recent trade dispute between China and the EU is over solar panel exports. In September, the EU launched a probe into alleged dumping of solar panels by Chinese manufacturers.

But Chinese manufactures refute the EU's claims, explaining that Chinese solar panels are cheaper than EU standards due to China's low labor costs. This led to the Chinese government filing a complaint with the WTO in November.

"I think organizations like the WTO need to be very active and robust in dealing against unilateral developments. China has been a member of the WTO for 10 years, and is beginning to use the WTO to act for its needs," he says.

Since his first visit to China in 2004, Greenaway has returned for regular visits each year. "The transformations were truly remarkable, particularly the investment taking place in infrastructure, transportation networks, IT, and quality of environment. I've never seen anywhere develop so fast," he says.

Despite his busy schedule, Greenaway tries to fit into each of his China visits an economics lecture to first or second year students at the university's Ningbo campus.

"It's important for me partly because I enjoy teaching. It's important also because it gives an opportunity to engage with the students, right at the beginning of their programs. And thirdly, I want to say in the most powerful way possible, teaching is important," he says.

He says that Chinese students are a joy to teach, which encourages his belief that China will become an innovative economy in the near future. "They're very attentive, listen very carefully to what you say, and are very good at asking questions. They are hungry to learn."

cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 12/21/2012 page32)

Today's Top News

- Xi stresses improving long-term mechanisms for cyberspace governance

- Experts share ideas on advancing human rights

- Japan PM's remarks on Taiwan send severely wrong signal

- Key steps to boost RMB's intl standing highlighted

- Sustained fight against corruption urged

- Xi calls for promotion of spirit of volunteerism