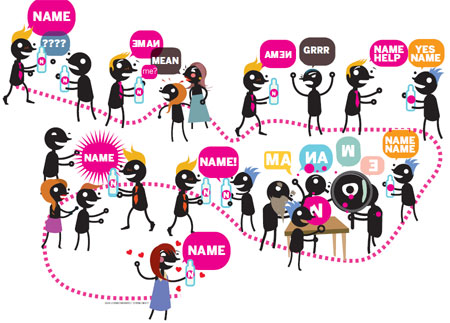

All in the name game

Nothing's lost in translation. In fact, the Chinese names of international brands can enhance a product's identity and give it new life

A white-collar Chinese urbanite might chat on his "Orion's Belt" while steering his "Precious Horse" toward a burger at the nearest "Grain at Toil". In other words, he might talk on his Samsung (sanxing) while driving his BMW (baoma) to McDonald's (maidanglao).

While these literal English retranslations sound amusing - or bemusing - to native speakers, they ring like music to the Chinese ear.

Multinational corporations have long been playing a name game to ensure their brand identities are not lost in translation when they enter China. Today, domestic enterprises are following suit as they become players in overseas markets. Consequently, demand for enticing English brand names is growing.

A scientific business has been devised around translating multinationals' names into Chinese - one in which perhaps thousands of proposals are developed before specialized consultants squeeze them through computer programs, multi-dialect linguistic analyses and focus groups to extract the best option.

But most Chinese enterprises aspiring to penetrate overseas markets simply ask their marketing teams to stab at something they hope works in English.

These self-translated brand names are like the company's children - bad or good, they're bred by them, Jiawen Translation Co's account manager Wang Yanchao says. Jiawen is among the few Chinese-to-English brand translators, but Wang points out that it's a tiny slice of its work.

Rather than crunch out quantitative and qualitative analyses, Wang usually hunts for transliterations (translations with similar pronunciations to the originals) that generate positive associations. Or he scours the Bible or Greek mythology for names with historical resonance.

He recalls selecting the English name for Chinese auto parts manufacturer Xinshiji, which literally translates as "New Century".

"New Century is widely used and isn't appealing enough," Wang says. "So, I gave the company the English name 'Synsky'. It's a similar pronunciation as the Chinese, and the prefix 'syn' suggests the company and its consumers share the same sky."

Globao senior consultant Amy Chen says her company will suggest English names for clients, but most will decide for themselves.

"These companies usually already have a clear idea of the name they'll use abroad," she says.

Senior translator Yao Zhang at Chinese Translation Pro believes: "Chinese companies don't seem to put as much weight on, and resources into, branding as Western firms, and are generally content with average English brand names."

Yao's company has translated the names of such juggernauts as Dow Chemical, General Motors and L'Oreal, but has never translated a brand from Chinese into English. Most domestic companies don't bother to translate their names.

Beijing entrepreneur Cheng Wei is CEO of both Beijing Shuilan Technology Ltd and Kaixin Yinfu music school. The growing music school has directly translated its name as "Happy Notes", despite not yet enrolling foreign students.

But Shuilan, which would literally translate as "Water Blue", hasn't conceived an English name although it contracts for Fortune 500 clients, such as BMW. "We never thought about translating Shuilan because we deal with multinationals' China operations," he says.

However, Chinese companies that directly market overseas often discover that it's advantageous to translate their names. Some contend domestic soft drink brand Jianlibao, which literally translates as "Health Strength Treasure", fizzled outside China because consumers couldn't pronounce it.

Perhaps because Chinese companies are leaving their national boundaries later in the game, their brand-name translation systems hail to the era when foreign companies started penetrating China.

Some translations from that era ranged from hilarious to harrowing. KFC's "finger-licking good" translated as "eat your fingers off", Time magazine reports.

"Come alive with Pepsi" was translated as "Bring your ancestors back from the dead", CNN says, while Coca-Cola's name was initially translated as "Bite the Wax Tadpole", language-study magazine The World of Chinese reports.

When that failed, Coke switched to "Wax Flattened Mare" and then arrived upon "Delicious and Happy (kekou kele)".

For Coca-Cola, it was a process that passed through names that sounded like nothing anyone would want in his mouth to a potion that everyone wanted to guzzle. The company had copious translation options, which would today be scientifically scrutinized in the sophisticated English-to-Chinese translation business.

As J.A.O. Design International Architects and Planners Ltd CEO James Jao puts it: "You don't want to be a laughing stock."

Taiwan's Economic Daily News this year awarded Jao's Chinese branding - Long An - as the Most Recognized Brand in Chinese Real Estate for the third year in a row.

Jao was born in Taiwan, gained US citizenship, studied marketing and became New York City's planning commissioner. He came up with "Long An" - a transliteration of Long Island that means "Peace Dragon".

J.A.O. Design not only scientifically scrutinized the name but also hired a geomancer to determine its auspiciousness according to its stroke number when written in traditional Chinese characters.

The flipside of the name's success, Jao says, is that 15 companies have copied it.

Consulted English-to-Chinese translations are generally pushed through vigorous gauntlets, Labbrand Consulting Co, Ltd's vice-general manager Denise Sabet explains.

The mission usually begins with a creative brief about the brand's characteristics and positioning, she says. It then examines whether it's more desirable to have a phonetic or semantic translation - or one that's both.

Then, the branding team brainstorms hundreds or thousands of candidates. They need as many as they can get for the next step - legal screening.

"The Chinese trademark database is becoming increasingly crowded, especially in popular categories, such as fashion and cosmetics," Sabet says.

"It's more and more difficult to find a name that hasn't already been registered."

Survivors are put to the flames of dialectical cross-referencing. Labbrand scrutinizes contenders in Mandarin, Shanghainese, Sichuanese and Taiwan dialects, and Guangdong's and Hong Kong's respective Cantonese, to avoid negative connotations - or baldly offensive meanings.

Next comes a consumer-marketing test to explore preferences. That's how Labbrand developed the Chinese names for such clients as Marvel. It arrived upon "Manwei", or "Comic Power".

"Together, the two characters are not only phonetically similar to the English name 'Marvel', but also indicate the nature of the brand and convey a sense of bravery and power," Labbrand's president Vladimir Djurovic says.

Stakes are perhaps higher for enterprises entering China, where names are like omens, pictographs contain broad yet deep implications and a few homophones create tens of thousands of words. So, translations are easier - and costlier - to mess up.

Djurovic points to Chcedo as a brand translation failure. "This naming strategy was a dead end, and they changed recently to Chando," he says.

Others point out Chando's Chinese name zirantang is similar to the Chinese pronunciation of Japanese cosmetic brand zishengtang, although the characters have distinct meanings. The Japanese brand literally translates as "Resources Birth Hall" while Chando is "Natural Hall".

It's not uncommon for Chinese enterprises to purposely assume foreign-sounding names, especially in the luxury market.

These homegrown companies are emulating multinational luxury brands, which often use foreign-sounding monikers in China to infuse exoticism into their allure.

"The car brand Lexus renamed itself in China to appear more foreign. At first, it was lingzhi and then it changed to laike sasi," Djurovic says.

Lingzhi translates as "Rise Ambition". The new name retranslates as "Thunder Overcome Bodhisattva Slovak" - a wild sounding ride, indeed.

Chinese brands are conversely discovering the blessings of international branding with no meaning in other cultures or positive associations. That, along with trademark concerns, was part of what inspired Legend to reincarnate itself as Lenovo - Latin for "The New".

"The phenomena of (brand translation from) English, Spanish, German and so on to Chinese that's dominant now will soon shift to be from Chinese to English, Spanish, German, etc," Djurovic says.

Currently, a mix of brand translations, mistranslations and lack of translations into and from Chinese - all with respective composites of pronunciation and meaning - is the norm.

But the future may be lurching toward global branding convergence in which, even if we speak unintelligible native tongues, we will all understand Brandonese and Brandlish.

Liu Qing contributed to this story.

erik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 11/16/2012 page24)

Today's Top News

- Xi stresses improving long-term mechanisms for cyberspace governance

- Experts share ideas on advancing human rights

- Japan PM's remarks on Taiwan send severely wrong signal

- Key steps to boost RMB's intl standing highlighted

- Sustained fight against corruption urged

- Xi calls for promotion of spirit of volunteerism