Seeing to believe

|

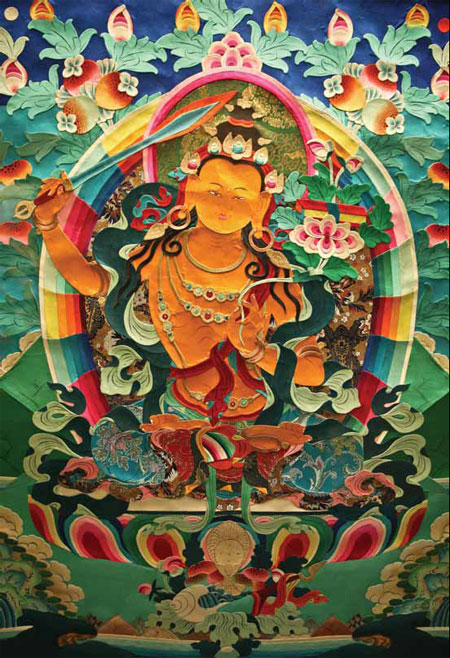

Green, blue, red and yellow make up the basic colors of Thangka. Ji Ruimin / for China Daily |

Tibetan art form continues to awe

The first thing you notice about the Beijing house of American designer Ken Jenkins has nothing to do with his country. Instead, it is an imposing scroll painting on the main wall depicting the Buddha in various postures, complex Buddhist symbols and grand Tibetan buildings. "I like collecting these kinds of paintings, or Thangka," he says. "Thangka is from the Tibetan language. These are magnificent works of art painted or embroidered on cloth, silk or paper. They are unique items of Tibetan culture."

|

Chinese scroll painting is kown for its substance and style. Its designs typically include flowers, birds, animals, beauties, landscapes and simple calligraphy that might show inspirational messages.

"But Chinese Tibetan Thangka art is considered even more special, and more foreigners such as Jenkins as well as Chinese collectors are rediscovering its beauty," Jenkins says. "It has distinctive Chinese ethnic group features and a strong religious flavor. It's also highly prized by Tibetans themselves."

Thangka can be seen in monasteries and Tibetan households. It can be traced back as early as the Songtsen Gampo period in the first half of the 7th century, as a combination of ancient Chinese scroll painting and Nepalese painting.

When the Tibetan patriarch Songtsen Gampo married Wencheng princess of the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), further strengthening the ties between the Tibetan and the Han peoples, the Chinese princess arrived in Tibet with numerous Buddhist scriptures, building technology, medical treatises and skilled artisans, significantly promoting the development of Tibetan society and Buddhist culture.

At that time, frescoes could not fully satisfy the needs of the religious. But Thangka was considered easy to carry, collect and display.

In the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, Thangka art experienced great development. The amount created not only increased significantly but also developed into many different schools and painting organizations. The Thangka that has survived today were mostly created during this time.

"Thangka can be divided into two types by the material: one is made of silk, called Gos-thang. And the other, called Bris-thang, is made of pigment," Tibetan Thangka painter Dawa Tsering says.

Gos-thang can be further classified into five forms according to the different kinds of silk. Tshem-drub-ma is made of various kinds of silk woven by hand; Dras-drub-ma is made of colorful silk patches connected with needles; and lhan-thabs-ma is similar to cloth-pasted pictures held together with glue.

Thag-drub-ma uses silk threaded by hand and Dpar-ma prints pictures into the silk through a special molding board.

"The largest Thangka of Gos-thang is called Gos-sku, which is too big to be hung up and only used at a number of grand religious rituals," Dawa Tsering says. "There is a very famous masterwork of this kind depicting the Amitabha in the Potala Palace."

But the Bris-thang type of Thangka is more popular.

"On the basis of background color, these can be divided into Tsho-tang, for multicolor backgrounds, and Gser-thang, which has a large area of gold. Mtshal-thang means the ground color is vermilion and Nag-thang's fundamental color is pitch-black. Dpar-thang is similar to water prints," Dawa Tsering says.

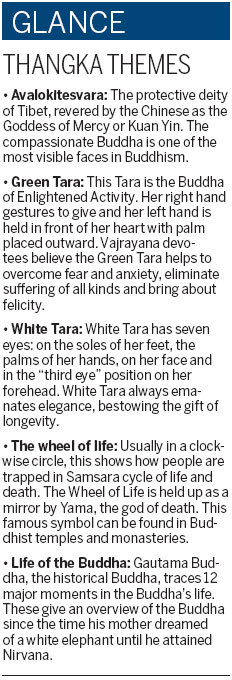

Thangka always has a theme of Buddhism, the images of great deities and Buddhas.

"So the composer must follow the sacred faith for portraying gods," Dawa Tsering says.

"Thangka features exact structure, solemn layouts, abundant content and distinctive drawing and painting styles."

Besides religious subjects, Thangka also reflect themes such as the biographies of important characters, historical events, Tibetan social customs, mythical tales and folklore.

Thangka is mainly painted using heavy colors with fine brushwork and line drawings. Besides color and printed Thangka, there are also embroidered, brocaded and pearl-infused examples. Collectors say authentic Thangka works of art can be preserved for decades or hundreds of years without any fading because its colors are refined from mineral stones. All the colors are mixed with animal glue and cattle bile to keep them bright. The natural mineral pigment is the essence and spirit of Thangka.

"Many Thangka are very expensive and hard to get," Dawa says. "Sometimes, fine gold, pure silver, precious stones, coral, pearls and other natural gems are added on the bright patterns to make the Thangka more splendid and glorious."

Apart from the material and color, different styles of Thangka can stand for different genres of paintings in Tibet.

In 2009 Tibetan Thangka art was put on the list of World Intangible Culture Heritage by UNESCO. In recent years, more exhibitions of the art have been held around China and attracted big Western audiences.

"Some travelers carry Thangka for protection and prayer. Its most important function is as a religious item in rituals or as an aid and guideline in meditation," says Wu Guojin, a Thangka collector and shopkeeper at Beijing Shilihe antique market.

"Each Thangka has its own connotation, moral and teaching, helping to soothe and quieten people's minds."

yinyin@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 08/31/2012 page24)

Today's Top News

- Experts share ideas on advancing human rights

- Japan PM's remarks on Taiwan send severely wrong signal

- Key steps to boost RMB's intl standing highlighted

- Sustained fight against corruption urged

- Xi calls for promotion of spirit of volunteerism

- Xi calls for promoting volunteer spirit to serve national rejuvenation