An unretiring type

| Sergio Amaral, chairman of the China-Brazil Business Council, says Brazil cannot blame China for buying its raw materials. Larry Lee / China Daily |

One of Brazil's most experienced envoys continues to advocate a healthy relationship with China

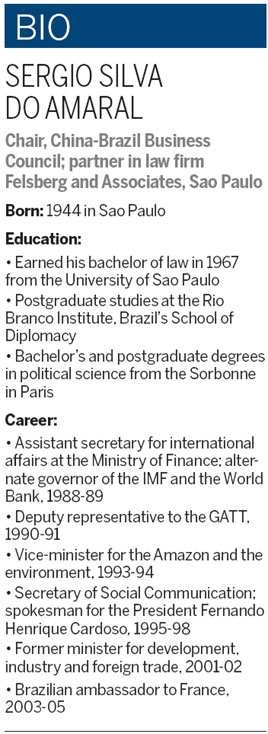

Sergio Amaral has had many high-powered jobs, including being Brazil's trade minister, the country's ambassador to France and Britain, its chief debt negotiator, chairman of the National Bank of Development and alternate governor to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

His public service days are over, but he is by no means relaxing, as he remains head counselor and board member of many institutions and corporations. Yet one of the jobs he devotes much time to is seldom mentioned in his biography.

As chairman of the China-Brazil Business Council for more than two years, Amaral, 68, wants to keep the two countries' economic and trade ties in a healthy state.

To him the China-Brazil relationship is both a big opportunity and a big challenge for his nation.

Bilateral trade between the two countries has grown exponentially in the past decade, from just $2.85 billion (2.29 billion euros) in 2000 to $84.2 billion last year, according to China's General Administration of Customs. This includes $31.8 billion of China's exports to Brazil and $52.4 imports from Brazil, a surplus of $20.6 billion for Brazil. Figures from Brazilian sources, while somewhat different, reflect the same trend.

China has been Brazil's largest trade partner since 2009, accounting for 17 percent of Brazil's exports, while Brazil has become China's ninth-largest trade partner and the largest among the BRICS nations, which also include India, Russia and South Africa.

The Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao predicted in June that the value of bilateral trade between China and Brazil is likely to reach $100 billion this year.

Meanwhile, China was the largest investor in Brazil in 2010 and 2011, with yearly investment well in excess of $10 billion. The momentum remains strong with last month's announcements that Lenovo, China's largest PC maker, will build a $30 million plant in Brazil to tap the third-largest PC market in the world following China and the US, and that Hafei Automobile of China will have its cars made in Brazil in a $122 million joint venture with CN Auto of Brazil.

Though the heavy content of primary goods - such as soybeans, iron ore and oils, which account for more than 80 percent of Brazil's exports to China - has drawn much attention, Amaral says Brazil cannot blame China for buying its raw materials.

"That doesn't make sense, if we blame Europe for not buying our commodities. We cannot blame China for buying. I think this (trade) is very positive," Amaral tells China Daily in his office at Felsberg and Associates, a law firm in Sao Paulo in which he is a partner.

Analysts say that while Brazil has satisfied China's needs for raw materials, the China trade has helped finance Brazil's economic boom in the past decade, during which commodities prices have remained high partly due to China's demand.

Though Brazil needs China as much as China needs Brazil, Amaral says some Brazilians cannot accept the fact that Brazil, as the first industrialized country in Latin America, exports chiefly primary goods to China while importing manufactured products from it.

But he admits: "This is partly our problem. China only dramatizes it, makes more explicit our vulnerability and our lack of competitiveness. It's not China's fault."

Brazil's overvalued currency, the real, the high interest rate, high taxes, inadequate infrastructure and strict labor laws make it difficult for its companies to compete with their Chinese rivals.

So when big Brazilian exporters benefit from booming trade with China, some small industrialists who cannot compete with China see their sectors disappearing.

"In many cases the Brazilian industries are upset. They are not productive and they are not competitive."

He also sees China's part in the problem. Some Chinese restrictions on Brazilian exports and investment have caused frustration, such as Embraer, Brazil's largest aircraft maker, not being allowed to produce its latest model in its China venture or Vale, the largest mining company in Brazil, not being allowed to directly distribute to Chinese buyers, having to go through a few Chinese agents.

Amaral would like to see China reduce its tariffs on finished goods so Brazil can export more processed food and soy oil to China.

The Brazilian government, under heavy pressure from its businesses to protect its domestic industry, has unleashed a number of protectionist measures against Chinese goods, including bringing anti-dumping charges against China in the World Trade Organization and imposing high tariffs on Chinese goods, the latest being one of up to 182 percent on footwear parts and accessories from China, announced on July 4.

However, Amaral, a counselor to the Federation of Industry of Sao Paulo, where the protectionist voice has been particularly loud, believes there are fewer problems between China and Brazil now than eight months ago.

When the Chinese Vice-Premier Wang Qishan visited Brazil in February for the meeting of the China-Brazil High-level Coordination and Cooperation, a bilateral talk first held in 2006, all the thorny issues were put on the table for discussion.

"I don't think we are going to have a productive meeting just to congratulate yourself that you are doing well, since the relationship is every important for both sides," says Amaral, adding that "it was very good, and both sides have made efforts".

In late June, when Premier Wen met Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff in Rio de Janeiro during the United Nations Rio+20 Summit, both sides emphasized their global strategic partnership. They also agreed on a common agenda of investments in mining, industry, aviation and infrastructure to boost commerce between the two countries. The two countries also struck a $30 billion currency-swap deal to facilitate bilateral trade and investment.

Many Chinese companies hope to tap Brazil's hosting of the World Cup in 2014 and the Olympic Games in 2016, and Amaral says there are many opportunities for Chinese companies to participate in the construction.

The Brazilian government is badly in need of foreign investment in many of the projects, and Amaral believes Chinese companies have an edge in the competition.

Amaral, who as trade minister led the largest Brazilian business delegation to China in 2002, now goes to China twice a year. He says the two countries are complementary, and believes a better way to achieve success is to form partnerships.

A recent study on Brazilian investment in China conducted by the China-Brazil Business Council concludes that Brazilian companies that have good Chinese partners are successful.

"So I think one way of improving our relationship and avoiding all these noises is we need to have a partner," Amaral says.

"Why can't we have a partnership in Brazil, or in China, for jointly processing for the Chinese market? A Chinese company knows much better than we do, for example what kind of products the Chinese market wants to consume. So why do we have to do it alone?" he says, emphasizing that Brazilian companies are very competitive in agriculture, including raising cattle.

He feels that cultural differences and lack of understanding have contributed to the problem. The business council he chairs has joined with the Confucius Institute in Brazil to educate local business people.

"You have to find a way to do this," he says. "Then everybody will gain."

chenweihua@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily 08/24/2012 page38)

Today's Top News

- Experts share ideas on advancing human rights

- Japan PM's remarks on Taiwan send severely wrong signal

- Key steps to boost RMB's intl standing highlighted

- Sustained fight against corruption urged

- Xi calls for promotion of spirit of volunteerism

- Xi calls for promoting volunteer spirit to serve national rejuvenation